Previously, in How to make things, we examined a technology, which specifies how inputs combine, in definite proportions, to produce outputs. But a technology is merely a static description. Let’s therefore breathe life into it.

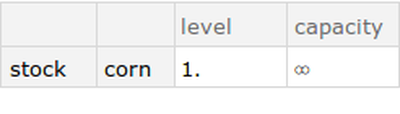

Consider this simplified technology:

To produce corn we need labour, preexisting corn (in the form of seed) and iron (in the form of hard tools and machinery). But these inputs are of very different kinds.

In particular, labour is different. Labour is the active agent that combines the iron and corn to make new corn. If the inputs failed to be combined together we would not blame the seed or the machinery. We’d blame the labourers, because they are the responsible agents that cause production to take place.

(This may seem an obvious point. However, the distinction between human labour and more complex inputs that also perform work (such as robots) can become very blurred. For now we’ll simply state that labour is a special kind of input, and make a note to return to this issue later.)

The unique nature of labour is reflected in how we measure its quantity. Corn and iron may be measured in tons. But labour is measured in units of time.

Human labour is a universal capacity that manifests in many different kinds of concrete activities. And a reasonably educated adult can supply labour to almost any area of the division of labour given sufficient training. So we measure the quantity of labour in units of time, such as hours or days etc.

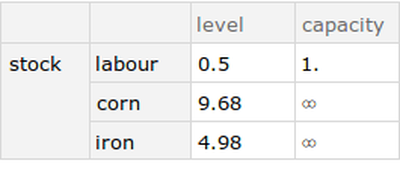

The farm labourer, therefore, sows new seeds in the field, and harvests the ripe corn that was planted in a previous period. For this to happen we need preexisting stocks of labour, seed corn and iron. Let’s say we have the following stocks:

Think of a stock as a “bucket” that holds some input resource. The corn stock takes the form of seed bags, and the iron stock is things like spades, hoes, tractor parts etc. The labour stock is one worker at the start of a working day. (In principle we can store as much corn and iron as we wish. But we cannot store multiple working days. So we limit the capacity of the labour stock to one working day).

Now we have all we need to actually produce some output. We have the right kinds of input stocks, and the technological know-how to transform those inputs into new outputs.

We command the production of 1 ton of corn. Post production we are the proud owners of 1 ton of new corn:

But some of our input stocks were used-up. When we inspect our input stocks we discover:

We’ve used up 0.5 days of labour, 0.02 tons of iron (wear-and-tear on hard tools and machinery), and 0.32 tons of seed corn. Why these precise amounts? Simply because the production process has an underlying technology, which defines the proportions in which inputs combine.

A production process is a simple description of a real work process. It captures the essential input-to-output nature of work that transforms input materials into output materials in useful ways. You may find it helpful to imagine the technology graph of Figure 1 has buckets placed at each node in the graph. The buckets are initially filled to levels that indicate the quantity of each input stock. As production occurs the substances in the input buckets (e.g., labour, corn, iron) slowly drain out, flow through the network, combine together, and reappear as new corn in the bucket at the corn node, which slowly fills up.

In summary, a production process is where labour transforms input stocks to new output stock according to a technology. We “activate” the process by commanding a certain level of output (in this example, 1 ton of corn). When that happens input stocks get used-up in proportions defined by the technology.

Next, we’ll examine how we can combine production processes into a single, self-reproducing system. Such a system uses-up inputs and produces an output, where that output is sufficiently “big” that it replaces the used-up inputs with something left over — a surplus.

1 Comment