I hope to write a follow-up article to my Venture Communism talk in the not too distant future. In the meantime, I’ve transcribed the talk, since I know many people would rather read text than listen to audio/video. So nothing new if you’ve already listened to the YouTube audio. Otherwise, hope you find this interesting!

The context: the crisis of working class organisation

I hold it self-evident that pluralism of political strategy is essential for the success of the socialist movement for the simple reason that no-one is certain about the future, which is radically open, and therefore — just like any other scientific discipline — the science of revolution should entertain multiple competing hypotheses regarding the best way to proceed.

Second, I also hold it self-evident that the historical data demonstrates that existing socialist political forms — such as reformist parties, militant unionisation, the worker co-op movement, vanguard revolutionary parties etc. — repeatedly fail to achieve the goal of overthrowing capitalism on a global scale (and, often, that isn’t even the goal). There’s a chance they might do one day, but that chance seems slim. Indeed, the historical experience suggests that, in practice, these forms either uphold or defend capitalist property relations, or construct social structures that manage to only temporarily abolish those relations and eventually collapse. The crisis of working class organisation is deep and longstanding — for those willing to look failure straight in the eye.

In consequence, I think it’s essential that some Marxists actually devote time to thinking, proposing, and experimenting with, new kinds of working class organisations. In my view, more of the total working day of the Marxist movement should be devoted to the project of searching for new kinds of political forms designed to abolish capitalism on a global scale. The opposite — that is funnelling more time and energy into existing socialist institutions — always has a short-term pay off, but that may come at the cost of losing the much bigger prize.

This is why Venture Communism is worth study. It’s a set of ideas first proposed by the software engineer, artist and activist Dmitri Kleiner in 2005. The point of Venture Communism is to develop a new type of revolutionary organisation that immediately allows workers to start to exit the capitalist system and enter a communal system, where the means of production are jointly and equally owned.

However, before we can really understand and evaluate Venture Communism, we first need to consider and understand Venture Capitalism.

Marx on the circuit of money-capital

Let’s begin with Marx’s analysis of the circuit of money-capital.

Money functions as capital, and becomes money-capital, when it participates in a social practice that uses money not merely as means-of-exchange but also as a principal sum that funds production for a period of time in exchange for a share of the profits.

A circuit begins with an advance of money-capital to purchase means-of-production and labour-power. Workers then add their labour, and transform the means-of-production into outputs, ready for sale in the market. Finally, and under normal circumstances, the output gets sold for a profit.

In consequence, the initial outlay of money-capital returns to the capitalist with a profit increment. This profit may then be spent on luxury consumption or invested to increase the scale of production (e.g., by developing or purchasing new means of production), or both.

Once a circuit of money-capital is up-and-running, it becomes a self-reproducing social practice, a kind of perpetual motion machine. The money-capital actually returns to the capitalist, ready to initiate a new circuit

This is absolutely wonderful if you are an owner of a large amount of capital. You can spread your risks over many circuits, sit back and enjoy above average returns in the aggregate.

Marx calls money-capital the ‘prime motor’ of capitalist production because it’s an engine that powers the accumulation of capital.

His analysis of the circuit is pitched at a quite abstract level, since he aimed to grasp the essential features of all possible kinds of circuits of money-capital. This partially explains why Marx does not specifically examine Venture Capital in any of the 4 volumes of Capital.

Also, although Venture Capital has, in one form or another, existed since the birth of capitalism, it wasn’t until after the Second World War that dedicated Venture Capital firms appeared in the USA.

In consequence, we find that Marx simply does not have much to say about the specific characteristics of Venture Capital or the birth of new capitalist firms.

Venture capital

So, what are the specific features of venture capital?

To start a new productive enterprise you need money. You need money to pay the bills until you have something to sell that generates revenue. There are a few ways to get access to capital. If you’re from a rich family then you can ask them. Or, an angel investor might supply some initial seed capital. Or, if you’ve got a track record, or already have some traction in the market, you can try pitching to venture capital funds. Venture funds prefer to invest in firms that are about to enter a significant growth phase.

For simplicity I want to lump all the private sources of capital together – and simply call them venture capital. Let’s define Venture Capital as capital that finances the growth of new or early-stage companies in return for equity, where equity is a share in the ownership of the firm.

Venture capital provides the very first initial outlay in a circuit of money-capital. Its a kind of bootstrap capital that initiates an entirely new circuit.

In this sense, then, Venture capital is the prime motor of the birth of new firms.

How Venture Capital reproduces capitalist social relations

But it’s not the prime motor of the birth of any kind of firm. It brings into existence specifically capitalist firms.

I’ll explain this with an example. Let’s imagine, for a moment, that we (you, I, and some friends) collectively want to start a widget-making business. We pitch the idea to Venture Capitalists, and they like it.

We ask for a 100,000 pounds loan. And we propose an interest-rate on the loan that includes an additional risk premium, since we recognize that our widget-making business might fail before we can replay the loan. We also propose that our firm’s assets, such as the widget-making machines we buy with the loan, will act as collateral. So if our business fails then the Venture Capitalists can reduce their losses by liquidating those assets.

Now, this seem like a fair proposal to us, especially given that Venture Capitalists spread their risk across a wide portfolio of new ventures.

Nevertheless, we wouldn’t get very far, and we’d be rather quickly ejected from their offices.

The reason is very simple. Venture Capitalists are not interested in extending loans to start-ups. What they want is equity – they want shared ownership of the firm. And ideally they want a controlling stake in the firm. The problem with a loan, from their point-of-view, is that it can be paid off. At which point, the firm is entirely ours, and they have no further claim on the profits that our labour creates.

In many ways, a loan is too much like an equal exchange for their tastes.

In stark contrast, equity gives them an enduring claim on the profits of a firm. Once they have equity they can claim a share of the profits of others labour for as long as they hold the shares, and for as long as the firm operates.

Equity capital is essentially exploitative. And this is why Venture Capitalists want it. And since they have a monopoly on the supply of Capital they demand it, and get it.

So we, who want to start our widget-making business, are faced with this external fact: in order to get funding we must incorporate a capitalist firm and allow owners of capital

to lay claim on the labour of others.

So it’s right here, at the moment of the birth of new firms, that capitalists inject exploitative property relations.

In fact, the major reason why worker co-ops are founded at a significantly lower rate compared to capitalist firms is that co-ops can’t get access to Venture Capital. Imagine you are a Venture Capitalist, and you have a choice between investing in a firm that give equity, and one that does not. The choice is clear.

But starting a worker co-op is not only more difficult. We also have to be saints. We have to decide to share profits with all the future workers that join or business, and therefore personally accept lower returns. We have to forgo the opportunity to exploit others, and potentially join the comfortable ranks of the capitalist class. In consequence, any group of founders need to be highly politically conscious, and also highly principled, to start a new venture that does not reproduce capitalist property relations.

The incentive structure of capital markets encourages both owners of capital, and owner of new entrepreneurial ideas, to incorporate specifically capitalist firms.

It’s no surprise, then, that despite all the well-known advantages of worker democracy, nonetheless capitalist firms dominate the economic landscape. It’s the differential birth rates, of these two types of institutions, that makes the difference. Capitalist firms are simply born at a much, much higher rate.

Venture Capital, in summary, is a pivotal moment in the reproduction of capitalist social relations. Dmitri Kleiner expresses this well in the following quotation:

“Capitalism has its means of self-reproduction: venture capitalism. Through their access to the wealth that results from the continuous capture of surplus value, capitalists offer each new generation of innovators a chance to become a junior partner in their club by selling the future productive value of what they create in exchange for the present wealth they need to get started. The stolen, dead value of the past captures the unborn value of the future. Neither the innovators, nor any of the future workers in the organizations and industries they create, are able to retain the value of their contribution.”

What if?

OK, that’s Venture Capital: on the one hand, a prime motor of capitalist production and the funding of new ideas many of which improve the quality of life, and push technical boundaries; on the other hand, it’s the prime motor of the reproduction of economic exploitation, the unequal distribution of income and wealth, and the parasitic extraction and basically theft of labour-time from the majority of the population.

Every time we allow our productivity to be taken from us in the form of profit we actively participate in our own oppression. This is the basic insight of Marx’s theory of profit and surplus-labour.

It seems to me, therefore, that a basic aim of Marxist political practice should be to build working class institutions that ensure our labour is not mixed with land and capital we do not own.

What if we could intervene at the point of the birth of new capitalist enterprises and change the incentive structure of capital markets? What if we could devise alternative social institutions that significantly increase the birth-rate of worker co-ops, and communal property relations? If so, it would it be possible to crowd-out the birth of capitalist firms, just as they currently crowd-out the birth of worker co-operatives? This, essentially, and as I understand it, is the explicit aim of Kleiner’s Venture Communism, which I can now turn to.

Venture Communism

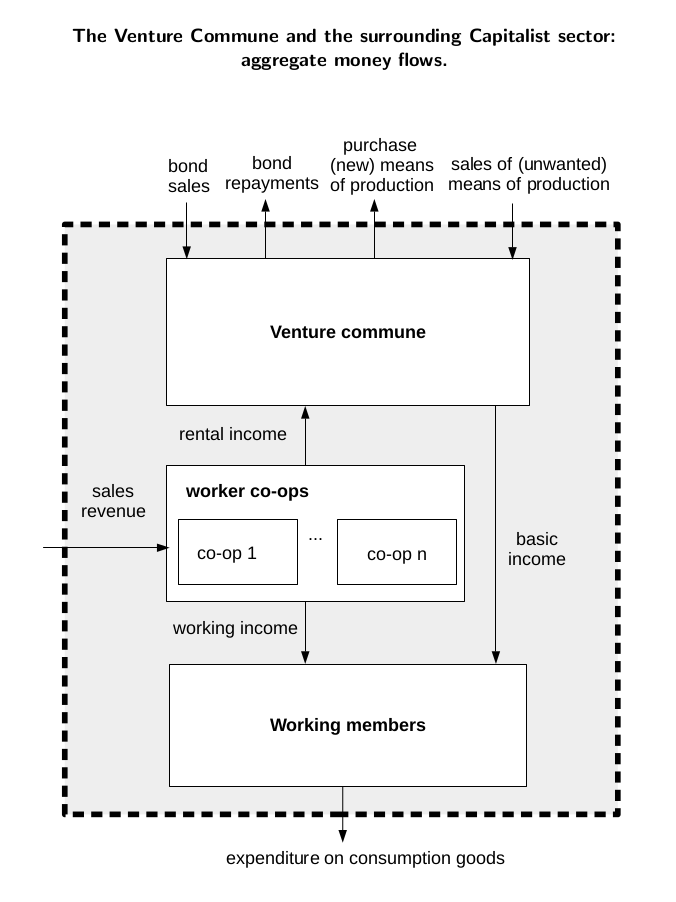

I’m now going to try to sketch an institutional structure, depicted below. Obviously I will skip a lot of detail.

Venture Communism is a type of voluntary workers association, which supports the collective accumulation of Land and Capital. It has 2 key institutions: worker co-ops and the commune itself.

The worker co-op

The first institution is the worker co-op. I won’t say much about the institutional structure of worker co-ops, especially as the variety of forms are relatively well-known and well-understood.

The key difference between a worker co-op and a capitalist firm is who owns what. The ideal worker co-op is collectively owned by its working members. In contrast, the ideal capitalist firm is collectively owned by its shareholders.

A capitalist firm hires-in human beings at a pre-agreed rental price, then sets them to work. The shareholders then claim the profits generated by this labour, solely in virtue of this paper claim, and independently of whether they contribute to production or not.

The capitalist owner earns income simply by privilege. As John Stuart Mill observed, the capitalist “earns money even as he sleeps.” A worker co-op, in contrast, reverses the contract between capital and labour. The worker co-op hires-in capital, rather than hiring in labour. The working members of the co-op claim the profits generated by their labour, which are then distributed to its members according to some kind of democratic divide-the-pie mechanism.

The key point is that worker co-ops are not exploitative economic institutions. For example, Marx, in Volume 3 of Capital, states that co-operatives “overcome the antagonism between capital and labour” and should be considered “as forms of transition from the capitalist mode of production to the associated one”.

The Venture Commune

The second key institution of Venture Communism is the Venture Commune itself, which is a democratic federation of worker co-ops and their members.

The first point is that all the property of the worker co-ops is collectively owned by the Venture Commune.

The Venture Commune itself is owned in common by every member. If you’re a member of the co-op then you’re a member of the Commune. For example, consider a small Venture Commune that consists of 2 worker co-ops. One is a bakery, the other a bicycle shop. The bakery and the bicycle shop employ 5 people each. All 10 workers therefore have an equal share in the Venture Commune. As a result, the total productive assets of all the co-ops is held in common by all the members.

And since every member has an equal share of the commune then all property is held equally. No member can accumulate a disproportionate share of the ownership of productive capital. Capital goods cannot be concentrated in fewer and fewer hands.

Some Marxists argue that if co-ops privately own unequal masses of capital they may exploit each other. So a market economy of worker co-ops does not fully abolish economic exploitation. Whatever the merits of this argument, it does not apply to transactions within the Venture Communism.

The role of the Venture Commune

The Venture Commune does not plan production at a microeconomic level. Instead, those decisions are decentralized, and subject to the discipline of the market, as in capitalist society.

The main function of the Venture Commune is the democratic stewardship of the common stock of productive assets. This includes activities such as acquiring property, loaning productive assets to worker co-ops, and liquidating property when it’s no longer needed.

The Venture Commune therefore exerts macroeconomic control over communal production because it manages the distribution and use of communal property. Let’s examine the most important example of this.

Back to our widget-making idea. We didn’t get very far with the Venture Capitalists because they wanted equity and we weren’t willing to give it to them. But we still need capital to acquire premises and buy the widget-making machines. So can the Venture Communists help us?

The Venture Commune rents-out capital

We pitch our business idea to a Venture Commune, and the members of the commune really like it, and think it’s a good business bet. After some deliberation they democratically vote to fund our start-up. So we’re in business.

However, the terms of the funding agreement offered by the Venture Communists are quite different from those that were offered by the Venture Capitalists.

The first difference is is that our new widget-making business will not own its own property. Instead, the Venture Commune releases some of its capital funds to acquire the premises and widget-making machines for us. The Commune then lends this property to our firm, and in return we pay the Commune a rental fee to use it.

The second difference is that although the Venture Commune owns the capital it does not own the worker co-op. The Venture Communists do not demand equity in the firm because they are ideologically opposed to appropriating the produce of the labour of others.

Instead, the worker co-op, as normal, is jointly owned by its working members. And in consequence, the Venture Commune has no claim on any residual profits of our newly incorporated widget-making company.

What’s happening here is something subtle but I think very important. First, the Venture Commune funds worker co-ops that hire-in capital, and pay out profits to labour. Second, the productive capital of the worker co-ops are held in common, and owned equally, by all the members. If anyone wants to use this common property they must rent it. Rent here is used as a mechanism to mutualize property.

What all this means, is that Venture Communism kick-starts a new kind of circuit of money-capital that reproduces the communal ownership of capital and the right of workers to retain the entire product of their labour.

Where does the money come from?

But where does the Venture Commune gets it capital from? How did it afford to buy the widget-making machines?

The short answer is that the Commune will get its money from wherever it can. The longer answer is that a Venture Commune, just like a newly incorporated Venture Capital firm, must initially raise capital from existing holders of capital, which ultimately means borrowing from savers, either small numbers of wealthy capitalists, or large numbers of workers, or both.

For example, a Venture Commune could raise capital by issuing its own bonds, in much the same way that established companies, or local governments, issue bonds to fund capital projects.

The capital that the Commune buys with the raised funds – such as premises and machinery – then serves as collateral to the bondholders.

The bondholders may be members or non-members of the Commune. If the Commune is of sufficient size then one could imagine an internal bond market, which would support

decentralized funding decisions.

The Venture Commune pays out on its bonds from the rental income it receives from its worker co-ops. Obviously, larger and well-established Venture Communes, with diverse portfolios, will do a better job of mitigating the risk of business failures, and therefore will have an easier time of raising funds through bonds. But new Venture Communes will face the normal economic challenges of starting at a small-scale and attempting to grow.

Once a bond reaches maturity, and pays out, then the bondholders cease to have any claim on the assets of the Commune.

Worker incomes

So that, very briefly, are the 2 key economic institutions. But what would it be like to be a member of a Venture Commune?

I’ll skip over the benefits of democracy in the workplace, or the significant social benefits of greater economic equality, since these are relatively well-known and understood. Instead, let’s consider a more basic kind of question: what money would you receive in exchange for your labour?

In Kleiner’s scheme it seems you’d have 2 sources of income. First, you receive working income in virtue of the labour you supply to the co-op. A share of the co-op’s profits are distributed to you, in a democratic divide-the-pie manner.

Clearly, the size of your working income depends on how well the co-op is doing, and how your peers value your contribution. Your working income will not be equal to other workers. Working incomes necessarily vary, since they depend on the supply and demand of specific skills, the rise and fall of particular business models, and also macroeconomic conditions, both in the communist and capitalist sectors.

The second type of income you receive is a kind of basic income, which you receive in virtue of your membership of the commune. Say that the commune, in the macroeconomic aggregate, makes a profit from its rental income. Then this aggregate profit is distributed to the members again in a democractic manner.

The growth aims of the communist sector

Of course, there’s a huge amount more that should be said about the political economy of the Venture Commune. But I hope what I’ve described so far communicates the general outlines of the Venture Communist system.

The aim of Venture Communism is to not merely survive within capitalism, as the cooperative movement has done, but in fact grow and accumulate wealth and power at the expense of the capitalist sector.

To achieve growth the Venture Commune must make a net profit with the surrounding capitalist sector.

Simplifying a bit, the Venture Commune will accumulate capital, and therefore grow, if two high-level conditions are met: (i) first, it presents the right structural incentives to encourage entry and discourage exit, and (ii) second, that its rental income is sufficient to pay out on its bonds.

The success of the Commune obviously depends on the commercial success of its co-ops. My feeling is that finding commercial success is the least difficult condition to meet. You eventually find commercial success if you fund a sufficient number of business start-ups. So really this is a numbers game. It will eventually happen given enough attempts.

On the other hand, getting the right structural incentives is absolutely essential and a more difficult condition to satisfy. Whether Venture Communism, as currently conceived, has the right institutional design to encourage entry and discourage exit is something of an open question.

Power not persuasion

So I will now come to a close with a couple of quotations from Kleiner.

First, Kleiner offers us a realistic and sober description of the real balance of class forces. He says:

“Any change that can produce a more equitable society is dependent on a prior change in the mode of production that increases the share of wealth retained by the worker. The change in the mode of production must come first. This change cannot be achieved politically, not by vote, or by lobby, or by advocacy, or by revolutionary violence, not as long as the owners of property have more wealth to apply to prevent any change by funding their own candidates, their own lobbyists, their own advocates, and ultimately, developing a greater capacity for counter-revolutionary violence. Society cannot be changed by a strike, not as long as owners of property have more accumulated wealth to sustain themselves during production interruptions. Not even collective bargaining can work, for so long as the owners of property own the product, they set the price of the product and thus any gains in wages are lost to rising prices.”

Kleiner then asks:

“So how can workers change society to better suit the interests of workers if neither political means, nor strike, nor collective bargaining is possible? They must refuse to apply their labour to property that they do not own, and instead, acquire their own mutual property. This means enclosing their labour in Venture Communes, taking control of their own productive process, retaining the entire product of their labour, forming their own Capital, and expanding until they have collectively accumulated enough wealth to achieve a greater social influence than the owners of property, making real social change possible.”

That’s it for now.

Reblogged this on Chronicles of The Vibe Shepherd and commented:

This is genius. A viable way to circumvent the need for and the trouble of violent revolution, which Lenin claims is the only way to secure a dictatorship of the proletariat. This blog post proves that Lenin is incorrect to make such a statement. A dictatorship of the proletariat could conceivably be achieved with enough transfer of labour to venture communism. This would be similar to the effect of a protracted general strike; for we know that one of labour’s major sources of power is its ability to withhold itself from the process of capitalist production and the generation of profit for shareholders. In much the same way, if labour were to divert itself into venture communes to a significant enough degree, then it would cease to be exploited by capitalists; the labour market would divide into two and supply of it to capitalists would entirely evaporate, since the offer of equity in venture communism would prove too attractive. The main difficulty for such a project seems to be securing the capital required to establish venture communes in the first place. But perhaps if enough workers come together and pool their funds, with some of them borrowing from larger capitalists, then that would be enough to get such ventures off the ground. It might even be profitable to seek out members of the labour aristocracy and solicit their involvement. Whatever the means, and they certainly exist, this is a promising path for the future of the communist movement.

LikeLike

The ruling class will use every means at their disposal to nip such a venture in the bud. They control the state. There will be legal hurdles, and if those are surmounted, naked repression. Look what happened to Allende when he tried democratic socialism.

That aside, how does this lead to abolishing the value form or what-have-you, and end alienated labor, when these cooperative firms are producing goods for exchange in the market? How do they survive market downturns? (They’ll need to have vast savings to keep members afloat, meaning less to reinvest in production, leading to inefficiency.) Capitalism seems more (and more) likely to collapse within the century due to known and unknown crises than it is to organically be outcompeted from within.

LikeLike

“The secret of change is to focus all of your energy, not on fighting the old, but on building the new.”—Socrates

LikeLike

Hi and thanks for your questions!

> The ruling class will use every means at their disposal to nip

> such a venture in the bud. They control the state. There will

> be legal hurdles, and if those are surmounted, naked repression.

> Look what happened to Allende when he tried democratic socialism.

Agreed. Venture Communism is no different in this respect from other form of revolutionary organisation.

> That aside, how does this lead to abolishing the value form or

> what-have-you, and end alienated labor, when these cooperative

> firms are producing goods for exchange in the market? How do

> they survive market downturns? (They’ll need to have vast savings to

> keep members afloat, meaning less to reinvest in production,

> leading to inefficiency.)

Venture communism does not, in itself, abolish the value form, just as other forms of working class organisations do not (e.g. revolutionary parties, unions, etc.) Venture Communism aims to immediately improve the material conditions of the working class by abolishing exploitation within the firm, creating new institutions of worker self-management, and increasing the independent economic power of the working class by socialising capital.

Many co-ops will not survive market downturns, just like capitalist firms. Venture Communes exist within the context of the rule of capital, and therefore must compete economically with the capitalist sector. However, any venture communes that collectively own the means of production of a large portfolio of co-ops, are much more likely to survive market downturns. Larger scale helps here. In fact, Venture Communes should strive to be immediately international in scope.

Right now the “vast savings” of the working class are funnelled into capitalist banks and pension funds, and those savings are then used to fund new capitalist firms, which exploit workers further. We’re literally saving in a way that increases the power of capital. The pooling of savings in Venture Communes, and the collective ownership of means of production, would radically alter this dynamic.

> Capitalism seems more (and more) likely to collapse within the

> century due to known and unknown crises than it is to organically

> be outcompeted from within.

Communist political practice is the conscious intervention in the real movement of history to hasten the abolition of capitalism. Venture Communism, in theory, contributes to that goal. Simply waiting for capitalism to collapse isn’t a wise strategy, especially as there’s no guarantee that it will collapse in a progressive direction.

Is it possible that a successful Venture Communist movement could out-compete the capitalist sector and grow at its expense? Speaking purely economically, there’s no reason why it could not. But as you point out, capitalists would move to kill it off. So a purely economic strategy is insufficient.

Historically, the working class, at least its most conscious elements, have innovated and tried many different strategies. Pluralism of strategy is important. And we must acknowledge the now long history of predominately abject failure in this regard. New ideas are sorely needed.

Venture Communes, in themselves, certainly do not create the realm of freedom, not even a limited realm of necessity within a socialist mode of production. Rather, they constitute a new form in which to struggle with capital, and weaken its rule, in the here and now.

Best wishes,

Ian.

LikeLike

“The secret of change is to focus all of your energy, not on fighting the old, but on building the new.”—Socrates

LikeLike

It’s good, but it’s worth considering that one venture commune may exploit another. And in my opinion it looks just the same as the right wing cooperatives.

LikeLike

I’ve been pondering the revolutionary potential of co-ops for a long time, so here’s a few points for your consideration.

Worker coops are not the only type of co-op compatible with anarchism/Marxism. There’s also housing co-ops. Where I live, Canada, all of a housing co-op’s equity is owned by the collective, no individual shares. Landlording is unique among capitalist scams in that failure is nearly impossible. Unfortunately, if a venture commune buys a building at today’s fucked up real estate prices, they’ll have to charge today’s fucked up rents. Over time as the mortgage is paid off the rent will drop. Once the commune has finished paying the mortgage they’ll be able to charge 55-60% of “market” rents while collecting a surplus comparable to property taxes. This can be a source of financing for the worker co-ops, or subsidize hard-to-make-profitable ventures like radical bookstores, art spaces, music venues… Another advantage of housing co-ops is they could buy a building with commercial space on the gound floor and residential space on the upper floors. As the mortage gets paid off the commune will gain the power to reduce the rents of worker co-ops located on their property. Revolutionary feudalism!

The foundation of any co-op movement, radical or centrist, is the credit union. Turnout/quorum for most credit unions meetings is quite low. This makes it easy a redical co-op movement to stack the agm of a small local credit union. This gives a reliablesource of financing, but comes with a problem I have not fully figured out. A credit union is basicaly a bank collectively owned by it’s customers, not it’s workers. This re-creates the owner/worker conflict of interest that we’re trying to avoid. Unionization will help, but the problemremains

Competition in a free market is not an accurate description how capitalism operates. Small businesses compete with each other in a very captured market but the corporations mainly buy politicians and use the power of the state to limit competition and guarantee their profits through subsidies, tax breaks, military contracts… At the same time the scale at which industrial production is potentially profitable has been getting smaller. There are now many opportunities to undercut corporate prices in a black market by violating the laws that prop up corporate profits. Easy examples would be pharmaceuticals or brand name clothing.

I could keep going but that is enough for now.

LikeLike