As all educated people know — the labour theory of value is false. Indeed, a hallmark of a university education, whether in economics or not, is a belief in the certainty of this proposition.

And yet, if you ask an educated person “the value question”:

What does one dollar, or one pound, measure or represent?

then you are likely to be met with a good few minutes of rambling and mumbling.

Everyone knows that the marks on a ruler measure distance, or a thermometer’s mercury column measures temperature, or a clock’s hands represent time. And inquisitive minds, before they are socialised to stop worrying about such things, naturally ask the value question and enquire about the nature of the numbers they find stamped upon the goods they buy, and the tokens they carry in their pockets. But unlike rulers, thermometers or clocks, few adults have a clear and distinct idea of the semantics of monetary phenomena, including economists.

Possible answers to the value question include “some specific thing”, “many things” or “nothing”. The history of economic thought has explored all these options.

However, the predominant attitude among economists today is value nihilism. “There is only price” and to seek something behind prices, to dig deeper, is simply a kind of confused essentialism. In consequence, to ask a modern economist the value question is akin to raising the issue of phlogiston with a modern physicist. It is anachronistic. Economic science once grappled with the value question but has subsequently educated itself to stop asking it.

The academy, at least within capitalist societies, turned against the classical labour theory of value during the 19th Century’s marginal revolution in economics. Subsequently, the labour theory has eked out a threadbare existence on the periphery of the academy, while enjoying robust and continued support from a small minority of intellectuals associated with the socialist tradition within civil society.

But even a resolutely pro capitalist academy, like we experience today, must appear to conform to scientific norms. So what reasons are normally given for rejecting the labour theory of value?

Simplifying, the academy normally offers two main reasons: one exoteric, and the other esoteric.

The exoteric reason is that market prices are determined by the Marshallian scissors of supply and demand. So prices are indices of scarcity, and therefore cannot represent the amount of labour time supplied to produce commodities. This kind of argument frequently appears in popular or “folk” rejections of the labour theory of value.

The esoteric reason is that Marx’s theory of the transformation doesn’t work. What is that theory? Marx understood that equilibrium (as opposed to market) prices of commodities systematically diverge from the labour time supplied to produce them. So the labour theory of value appears false on the empirical surface of capitalist society. Yet Marx argued that this divergence is merely apparent and caused by the distorting effect of capitalist property relations. In his unfinished notes, published as Volume III of Capital, he proposed that prices are conservative transforms of labour time (i.e., prices are “transformed” expressions of labour time). So although the prices of individual commodities and labour times diverge, there is a one-to-one relationship between prices and labour times in the aggregate.

The father of neo-classical economics, Paul Samuelson, published articles in the 1950s and 70s that, although not original, demonstrated in mathematical terms that Marx’s theory of the transformation cannot work, and therefore there isn’t a systematic one-to-one relationship between equilibrium prices and labour time.

Unsophisticated critics of the labour theory will offer the exoteric reason, but more sophisticated critics know the scarcity objection doesn’t hold water. So sophisticated critics ultimately defer to Marx’s transformation problem.

But here’s the rub. The critics have a point. Marx’s theory of the transformation is indeed incomplete and does have its problems — a feature that Marx first pointed out himself in his own notes.

From a sociological point of view, and simplifying greatly, we have, on the one hand, a pro capitalist academy eager to excise the labour theory of value, and all its radical implications, from academic discourse; and, on the other hand, a pro Marxist periphery motivated to defend the theory against the ideological attacks of the ruling elites. The environment for pursuing the science of the theory of value is decidedly unhealthy. But it could not be otherwise.

An unfortunate trend in Marxist circles, which represents a real obstacle to material progress, is to “wiggle out” of the transformation problem via creative reinterpretation of the meaning of Marx’s texts. Many reinterpretations attempt to save Marx only by dismantling the scientific content of Capital. For example, a large family of reinterpretations end up denying that labour time is a market-independent property of reality. So much for materialism.

So why is the labour theory of value true? I give a brief, technical answer in this new position paper:

The General Theory of Labour Value

Some of the main points are:

- The classical labour theory of value is a special case of a more general theory.

- The general theory:

- dissolves the transformation problem in a natural and transparent manner,

- preserves Marx’s theory of exploitation and surplus value,

- demonstrates that equilibrium prices and labour times are dual to each other (this is a theorem), and

- reveals how the dynamics of capitalist competition instantiate a lawful relationship between scarcity prices and labour time (i.e., it reconstructs Marx’s “law of value”).

- In consequence, the general theory establishes the logical basis for answering “labour time” to the value question.

The modern nihilist attitude does not represent a sophisticated rejection of naive substance theories of value but instead signifies the continued existence of unresolved and fundamental theoretical problems that first manifested at the birth of modern economic science in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

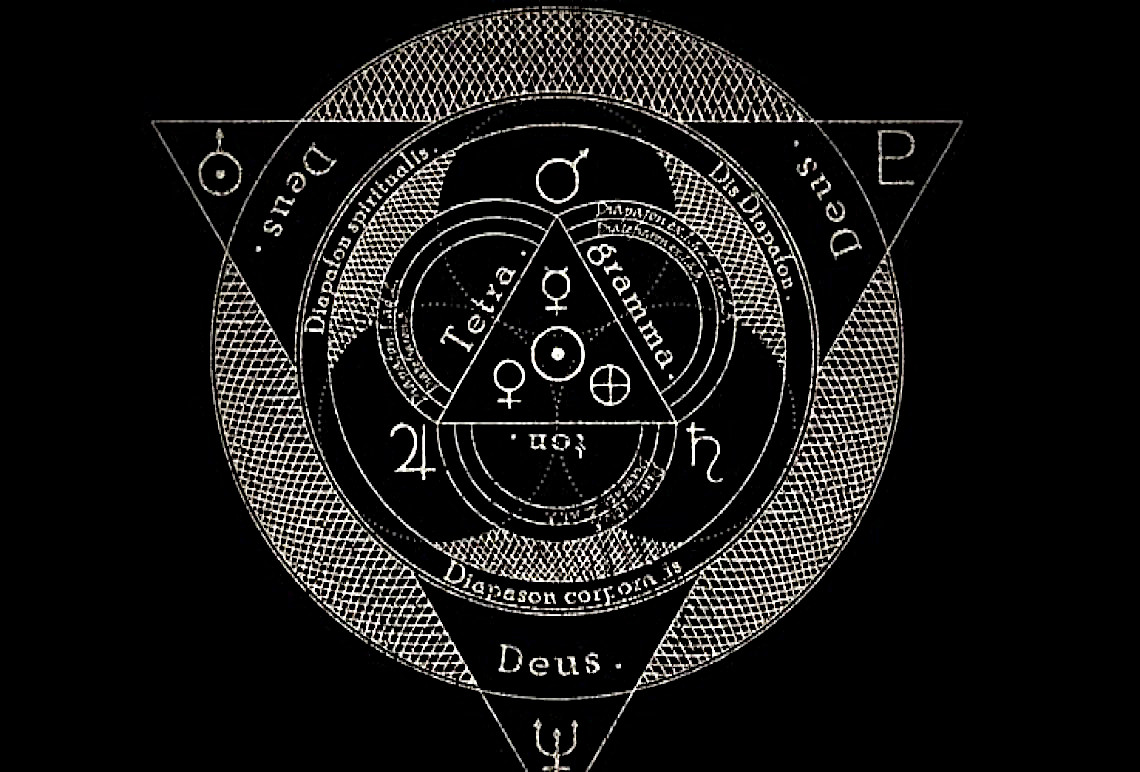

There is no royal road to science. And the unfortunate truth for the pro capitalist academy is that the road to a scientific understanding of the economy passes through Marx. There’s no way around him, because, of all the economic thinkers, he got the fundamentals of the theory of value right. And every modern school of economic thought, whether orthodox or heterodox, is woefully ignorant of what the unit of account actually signifies. We are like blind ants who obsess, suck and exchange the Queen substance, yet know nothing of its true function. Marx stands on the road ahead, pointing in the direction of a truly scientific understanding of the kind of society we live in. That’s why this post has a picture of a coin with Marx’s head on it.

Reblogged this on East Side Marxism.

LikeLike

Hi,

I’m confused. After reading yours and other Marxist explanation for LTV I’m unclear as to how LTV relates to scarcity: for example the price of large diamonds. Also how the theory relate to house prices and price ‘gouging’ .

LikeLike

Thanks for your question!

The paper shows that market prices, which are indices of scarcity, are continually “pushed”, by the dynamics of capitalist competition, to equilibrium prices that directly relate to labour time. The rate at which the scarcity price of a commodity dissipates depends on the rate at which its supply can be increased. We don’t observe an economy in price equilibrium. So we expect to empirically observe market prices, which are determined by supply and demand, and which will not directly relate to labour time. My post

steps through this in more detail.

I hope this answers your question! Please follow up if anything is still unclear.

-Ian.

LikeLike

Thank you for taking the time to reply. The post you link to raise another question, that of non-reproducibles- which I guess is what I was asking when referring to diamonds. “How can a labour theory of value handle non-reproducibles, such as land, or unique works of art? “

LikeLike

Hi! I’m a student from Italy

I read your paper “The general theory of labour value” and I found it very interesting.

May I ask you one question about it?

How could you establish workers and capitalists’ consume bundles before knowing prices?

While reading the numerical example you provide at the end of the paper, I noticed that you put both classes’ consumptions in physical terms among the hypothesis* and consequently you manage to find profit rate and prices.

I think that in free market you cannot know ex ante what and how much workers and capitalists are going to consume: only ex post, when net product is available on the market, you’ll see what the breakdown between classes will be like in terms of consumptions.

Maybe you actually can demonstrate that it is possible to identify the physical the consumption bundles of every class, but not simply by putting it among the hypothesis.

If you do so, I then could ask you why capitalists and workers should have decided to acquire that specific amount of each commodities, instead of getting more (or less) of it? I mean, my opinion is that this should be a result, not a starting point.

Otherwise it’s not easy to prevent someone from arguing that it is precisely wages and profit rates that determine the amount of consumption.

Am I wrong? Did I misunderstand what you wrote?

I thank you so much for your attention

*I am referring to: ” w = [1, 0.05] and c = [0.5, 0.1] ” (page 9 in the paper)

LikeLike

Thanks for your great question!

> How could you establish workers and capitalists’ consume bundles before knowing prices?

Quick answer: I don’t.

Long answer: I assume that households want to consume a definite selection of commodities in given proportions. And I assume the commodities are perfect complements (this is a simplifying assumption). But we don’t fix the scale of consumption (i.e., the actual quantities of each commodity that are consumed).

E.g., We assume that workers consume corn and sugar, and that they consume 2 units of corn for every unit of sugar. But how many units of corn and sugar they actually consume will depend on market prices and their money stocks.

So real consumption varies along a fixed ray in quantity space (where each dimension of that space is a commodity).

> While reading the numerical example you provide at the end of the paper, I noticed that you put both classes’ consumptions in physical terms among the hypothesis and consequently you manage to find profit rate and prices.

The numerical example is for a steady state equilibrium. So the economy is repeating, unchanged over time.

We then observe the actual bundle of commodities consumed by the different classes in this steady state. From this information, and knowledge of the technique, we may compute super-integrated labour values.

The motivation for this numerical example is to demonstrate that super-integrated labour values are objective, or “physical”, properties of an economy, which may be operationalised independently of the price system. But there is no theory of income distribution here. We just take the distribution as a given.

> If you do so, I then could ask you why capitalists and workers should have decided to acquire that specific amount of each commodities, instead of getting more (or less) of it?

The dynamic model has an (implicit) theory of income distribution, which controls what each class gets, both during convergence, and in the steady state. For more details I suggest you look at Chapter 7 of my thesis

https://sites.google.com/site/ianwrightoxford/research/2016-thesis

I hope this answers your question! Please follow up if anything is still unclear.

-Ian.

LikeLike

Hi Ohu

Thanks for your follow up question:

> “How can a labour theory of value handle non-reproducibles, such as land, or unique works of art?”

I plan to address this issue in detail in future blog posts. But, for now, allow me to give the standard, classical answer.

The supply of non-reproducibles cannot be increased by the reallocation of any additional labour or capital resources. In consequence, the price of a non-reproducible will not converge to a natural price but instead will persist indefinitely as a market price determined by supply and demand. So owners of such non-reproducibles will enjoy economic rents even in equilibrium (however defined). In this sense, non-reproducibles are not subject to the law of value.

The classical authors, such as Ricardo and Marx, developed their theories of rent to account for the price of non-reproducibles. Marx, for example, viewed rent as a deduction or extraction from the surplus labour produced by workers.

But the law of value isn’t entirely negated. For example, high-rise buildings, and poster reproductions of fine art, are some obvious examples that indicate that non-reproducibles are continually subject to attempts to increase their supply by the reallocation of more labour time to their production.

The marginal revolution subsequently took Ricardo’s theory of rent and generalised it to apply to all commodities (and deprecated the vision of the classical gravitation of reproducible commodities). Yet merely stating that price is determined by supply and demand is vacuous as a theory of value (as the classical authors understood).

I think the classical answer is OK, as far as it goes. But I also think more can be said …

Best wishes,

-Ian.

LikeLike

Hello Ian. I have just finished working through the equilibrium portion of the paper and have a few comments and questions.

1. Is there a reason why the nominal wage is assumed to be exogenous in the model? To my way of thinking, the equilibrium nominal wage is another quantity that needs to be determined by the system of production and money vs. commodity exchange, and so it should be derived within the model. You are probably already aware of the role of value theory in determining the nominal wage magnitude, so I’m curious as to why you chose to leave it out of the analysis.

2. Ideally, the model should be made more general by incorporating expanded reproduction, but that would involve additional difficulties. For example, there is the question of whether labor used to expand the scale or production or develop new products (i.e., labor included in Pasinetti’s subsystems) would then need to be included in equilibrium price determination. Have you made any exploration of this area?

3. Isn’t the term capitalist consumption misleading in a way? It makes it sound as if capitalist are similar to households with the possible exception of more luxury goods consumption. To my way of thinking, a more general term would be capitalist class reproduction, given that capitalist corporations spend a huge amount on taxes, legal services, anti-union and anti-redistribution political discourse, etc.

4. How would the classical economic category of unproductive labor fit into your analysis? To my mind, unproductive labor as analyzed by Marx can be put into three categories: (a) labor to maintain the survival of individual commercial firms, regardless of class structure (e.g., commercial advertising, insurance, etc.), (b) labor to reproduce the conditions of expansion of commercial firms, regardless of class structure (e.g., spending on R&D, marketing, outreach, the financial system, etc.), and (c) capitalist consumption/class reproduction as described above. Would you include just one, two, or all three categories in the area of capitalist consumption?

That’s all. I’ll have more questions and comments once I work through the dynamic model. Thanks,

Andres

LikeLike

Hi Andres,

Thanks for your detailed comments!

1. The nominal wage is endogenous in the complete model, i.e. its equilibrium value is an outcome of the dynamic adjustment rules specified in the second part of the paper.

2. Yes and no. Yes, since I’ve applied my approach to Pasinetti’s growth model; see https://ianwrightsite.wordpress.com/2017/06/13/luigi-pasinetti-and-the-labour-theory-of-value/ . No, since I haven’t (yet) extended this particular dynamic model to include investment goods etc.

3. I think you make a valid point. Yes, “capitalist consumption” is intended to cover all capitalists’ personal consumption – of whatever kind. However, the majority of “taxes, legal services, anti-union and anti-redistribution political discourse” appears on the cost sheets of enterprises, and therefore, in a social accounting matrix, constitutes part of firms’ input costs, and therefore does not count as a component of capitalist consumption.

4. I think Marx’s concept of “unproductive labour” is not fully consistent, and here I follow Rubin. There’s a lot of confusion around this issue. If I recall correctly, Marx, in his unfinished notes published as Volume 3, appears to use both (i) a normative concept of unproductive labour (labour supplied solely in virtue of capitalist property relations, e.g. some kinds of guard labour employed to prevent theft) with (ii) an empirical concept (labour supplied to a capitalist that doesn’t yield a profit for them, e.g. Bill Gates’ expenditure on his domestic retinue). In the context of super-integrated labour values, which are empirical measures of labour costs linked to the actual accounting practices of a capitalist economy, we only include (ii) as part of capitalist consumption. Note however that, in the more general theory, we continue to use classical labour values to make important normative claims, such as calculating the reduction in the length of the working day that could be achieved by abolishing capitalists’ hyper consumption, while keeping the workers’ real wage constant.

If you have any further comments I would be very glad to get them.

Best wishes,

Ian.

LikeLike

As someone familiar with the scientific side of things I’d really like to know your take on George Caffentzis’ book ‘In Letters of Blood and Fire: Work, Machines, and the Crisis of Capitalism’, here: https://libcom.org/files/in-letters-of-blood-and-fire.pdf

The part two, and particularly the article ‘Why Machines Cannot Create Value: Marx’s Theory of Machine’.

This issue of the Commoner and his article are also related to this: http://www.commoner.org.uk/?p=22

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Chris

Thanks for raising the issue of whether machines create value.

Since Turing this question has become more acute. I have worked in Artificial Intelligence all my life. And although truly intelligent machines are a long, long way away, I also know that — in principle — any concrete human labour activity may be replicated by machines.

So, from a materialist perspective, we might think that whether an activity is performed by flesh or by metal makes no difference, and therefore machines can create value, contra the Marxist tradition.

For example, let’s say Uber manages to perfect its self-driving technology tomorrow. Uber fires all the human drivers. The Uber cars still ferry people from A to B, and Uber charges the same prices. So its profits are the same. Surely the self-driving cars now create the same value once created by the human workers?

I am aware of some of the work you cite. I haven’t read any work that fully gets to grip with this issue. So I think I need to put my thoughts down, which will take a few blog posts. So I hope to answer your question in the future.

For now, however, let’s make a note of the important empirical fact of the negative correlation between sectoral profits and the organic composition of capital. In other words, sectors that employ more (resp. less) machinery relative to labour tend to have lower (resp. higher) profits.

Best wishes,

-Ian.

LikeLike

You’ve not addressed any of George Caffentzis arguments: https://libcom.org/files/in-letters-of-blood-and-fire.pdf

The relation between Marx’s theory and Mid-nineteenth-century thermodynamics is addressed in his paper.

LikeLike

Hi Chris,

About four years later I got around to addressing Caffentzis’ argument that human labour uniquely creates surplus-value because it can uniquely withdraw it. I don’t mention Caffentzis explicitly in this talk (because others’ have made a similar argument) but I explain why it doesn’t establish the conclusion, and also why it doesn’t link to the actual content of Marx’s theory of surplus-value.

Best wishes,

Ian.

LikeLike

Hi Chris,

You are right I didn’t. I hinted that I would in a future blog post.

But if there are specific arguments of Caffentzis you’d like me to respond to right away, then please feel free to raise them here.

Best wishes,

-Ian.

LikeLike

Hi Ian. I finally got through the dynamic model portion of the paper. A few more questions and comments:

1. First, I am mystified by the different treatment of the profit rate in the dynamic model compared to the equilibrium model. In the latter, the profit rate is endogenous and determined by the W and A matrices. In the dynamic model, however, the profit rate is an exogenous interest rate. I’m not sure that it matters whether capitalist households appropriate all firm revenues and then lend back the circulating capital to the firms, or if they simply appropriate the residual income as dividend profits while letting firms hold on to the circulating capital. More importantly though, there is no mechanism for allowing the interest rate to converge dynamically with the equilibrium profit rate determined by the (I – A – W)(A + W)-1 matrix. So unless I’m mistaken, the dynamic model only leads to full convergence if the initial interest rate r(0) is arbitrarily set equal to the equilibrium profit rate. Let me know if I’m making an error here.

2. Harking back to my question from previous comments, while the dynamic model does show how prices tend to move over time so as to satisfy Theorem 1 (assuming that r(0) is equal to the Lemma 1 profit rate…) I still think you need a similar result for the nominal wage, which would more satisfactorily link the nominal wage as a commodity price to the general labor theory of value. As it is, the equilibrium wage in the dynamic model is determined entirely by supply and demand: L vs. lqT and by the wage elasticity, i.e., superficially. That is, there has to be a proposition determining the nominal wage as a function of technical consumption (the A and W matrices) and the ratio of monetary circulation to the working day.

3. Also with regards to the dynamic model, I was wondering if you have formulated a reply to those economists who don’t believe in a well-functioning invisible hand and would therefore not tend to believe in the Law of Value either, even for the general vs. the classical labor theory of value. I have in mind mainly post-Keynesian economists sympathetic to value theory such as Victoria Chick and Colin Rogers (whom you cite) as well as other post-Keynesian economists such as Paul Davidson (who are skeptical of value theory), both of whom would stress that (a) it is not clear that capitalists will set prices so as to maintain stable inventories when they can instead change the pace of production to do so; (b) conversely, that output adjustment reacts to aggregate demand within each industry rather than to profit rate differentials; (c) the Phillips Curve mechanism has little if any effect on wage dynamics, which are mainly determined by inflation and by labor vs. capital power distribution within industries, which are unchanged even if the economy is near full employment; (d) assuming a passively adjusting money supply, interest rates are set mainly by the extent of financial intermediation in the economy and by uncertainty within the financial system, and would thus not have any direct relationship with the industrial profit rate.

4. Moving back to the general theory and the equilibrium model, you state that the classical (Ricardo/Marx) labor theory of value fails because prices are also determined by class conflict over the distribution of income. Is this actually the case? The worker and capitalist consumption matrices W and C are in my opinion determined mainly by social convention rather than class conflict, i.e. the necessary goods and services needed to reproduce worker households and capitalist property relations. If the general labor theory is to be useful as a long-term guide to prices, then these matrices should be relatively invariant (i.e., they should change only if the production technology and product range change), while actual class conflict would only lead to chronic deviations from this technical distribution of income. So it seems to me that if the general labor theory of value is to be a useful explanation of both long-term prices and exploitation, it has work with underlying assumptions that are independent of class conflict (which is of course very real); otherwise it is a foundation based on quick sand.

That’s all. Thanks for all your hard work on this subject, and I look forward to seeing more,

Andres

LikeLike

Hi Andres,

Thanks for your additional great comments. I very much appreciate you taking the time to understand my work.

1. I think you may have misunderstood some aspects of the dynamic model.

You state: “in the dynamic model, however, the profit rate is an exogenous interest rate”. That’s not correct. In the dynamic model, profit has two separate components: interest on money-capital supplied, and industrial profit (the difference between firms revenue and costs). So the profit rate is different from the interest rate.

This difference expresses different property relations: profit in virtue of money capital advanced, in contrast to profit in virtue of the ownership of the firm. The former is an ex ante cost of production, whereas the latter is an ex post residual. The different property relations are the material basis of the differentiation of the capitalist class into financiers and industrialists.

In my dynamic model, industrial profit is the difference between firm revenues and costs (which include interest payments on loan). Industrial profit is a disequilibrium phenomenon (unlike some Keynesian models I avoid explaining profits in terms of conventional mark-up pricing). Hence, you correctly observe that “there is no mechanism for allowing the interest rate to converge dynamically with the equilibrium profit rate”. That’s because the equilibrium profit rate is zero — classical macrodynamics, it turns out, instantiate a tendency for the profit rate to fall.

In Chapter 7 of my thesis

https://sites.google.com/site/ianwrightoxford/research/2016-thesis

the interest rate is endogenous (as opposed to fixed in this case), and therefore varies over time. Note however this is a classical model based on a loanable funds theory of the interest rate, and therefore doesn’t model a modern capitalist economy with its developed financial sector.

One of the problems with static, linear production models is that they necessarily conflate industrial profit and the interest rate in an equilibrium setting. So the distinction between interest as a cost and profit as a residual is often completely neglected.

2. The disequilibrium wage rate is indeed determined by supply and demand in the market for labour. In this respect, I simply follow Marx: “the same general laws which regulate the price of commodities in general, naturally regulate wages, or the price of labour-power. Wages will now rise, now fall, according to the relation of supply and demand, according as competition shapes itself between the buyers of labour-power, the capitalists, and the sellers of labour-power, the workers” (Wage Labour & Capital).

However, the equilibrium wage rate is independent of the out-of-equilibrium fluctuations in the supply and demand for labour, and is determined by elasticity and the equilibrium level of employment (supply and demand affects the trajectory of the wage rate but not its final level). The equilibrium level of employment depends on all the determinants of the equilibrium of the dynamic model. The equilibrium is the solution of a 2n+1 system of nonlinear simultaneous equations (fully described in proposition 14 of my thesis). This system has some interesting properties, which I briefly mention in section 7.2.7.

In fully dynamic models the out-of-equilibrium differential equations will, in general, implicitly define a quite different set of equilibrium simultaneous equations. So the equilibrium level of employment is not determined “superficially” as you state, and there are propositions that link the wage rate to technical consumption (in equilibrium).

3. I began to study post-Keynesian models but found there are few properly dynamic models in this literature, and so I lost interest. Causal claims are made without proper justification (since often they are based on conceptually faulty comparative statics, as per much of neoclassical theory). Plus, this tradition is also hardly interested in the theory of value. Steve Keen is an interesting exception.

On the other hand, most post-Keynesian models focus on more complete models of a capitalist economy (which, as you mention, include a financial system, central bank etc) and it is necessary to introduce such institutions in order to make less qualified statements about capitalist (as opposed to classical) macrodynamics.

4. The general theory is intended to preserve the existing theoretical infrastructure and extend it, and therefore includes both classical and super-integrated measures of labour value, where these have different theoretical roles. For long-term determinant of profits (and exploitation) I think classical labour values are the foundation (which are independent of class conflict). As an example of this approach, I point you to the work of Peter Flaschel; e.g.

https://www.marx-capital.eu/

especially his work on the long-term determinants of the profit rate, and also his work linking classical labour values to Richard Stone’s system of national accounts.

Note that the equilibrium of the dynamic model we’ve been discussing is not, in my opinion, a long-term or “long period” state. It never manifests. Rather, it’s an attractor state. One role for super-integrated labour-values is to demonstrate that — even when an attractor state is partially determined by conflict over the distribution of income — the resulting price dynamics do not invalidate the labour theory of value (contrary to many authors in the post Sraffian and PK tradition).

Thank you for your comments. These issues are very subtle, and no-one has a monopoly on the best way to proceed. I admit I have a jaundiced view of most of the PK tradition, but there are good parts, and I’m sure I can learn some things.

Best wishes,

-Ian.

LikeLike

heterogenous labour*

LikeLike

Hi Ian, how can we measure heterogenous value in a input-output table in relation to the labour theory of value?

Thanks,

Kumar

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Kumar,

Thanks for your question. What do you mean precisely by “heterogeneous value”? Do you mean (i) heterogeneity of production techniques for a commodity type, (ii) heterogeneity of wage rates both within and between sectors of production, (iii) heterogeneity of worker consumption bundles, or something else?

Thanks!

Ian.

LikeLike

Hello–– In regards to the LTV I had a few questions. (you may have went over some of my questions in your 200 page thesis paper, but parts were incredibly technical and hard to understand, I hope to do some reading on linear algebra and differential equations to get a further grasp on your general theory of value)

1) In chapter 1 of volume one of Capital, Marx briefly goes over the distinction between skilled and unskilled labor, saying that skilled labor was simply intensified unskilled or simple labor. The way I took this is that the concrete labor times of skilled workers would be less than the amount of value creating substance congealed in the commodity. Let’s say “a” represents the value of 1 hour of unskilled labor, or the average labor power of a worker. Let’s also say that “b” represents the value of 1 hour of skilled labor. Marx is claiming here that

b = x*a, x being the constant determining how skilled b is in relation to a. My question here is, how do we determine “x” in order to empirically measure and corroborate the LTV. In other words, how can we find one unit of homogenous abstract labor in order to empirically test the theory of value?

2) Marx held a theory that there is a gravitational pull in an economy for sectors to have uniform profit rates. This conception that Marx had (which led to him making the specification of “prices of production” in volume 3) has been contested in literature, independent of the transformation problem. The Neo-ricardians reject that there is a tendency toward uniform profit rates. My question is, is there a tendency in the economy for profit rates to equalize in the long run? can you point me to the literature contra or in defense of this uniform profit rate theory?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Adheep,

Thanks for your questions. (1) is sufficiently interesting that it deserves a separate note, especially as Marx adopts multiple, different stances on this question. I’ll reply in a future blog post. (2) Not only Marx, but classical economists and also modern economists (in the guise of zero arbitrage in equilibrium) assume there is a tendency to equalise rates of return. Neo-Ricardians typically do accept there is a tendency to uniform profit-rates. My view is that the structural logic of capitalist competition instantiates a profit-equalising tendency (see my dynamic model of the general law of value). However, the empirical profit-rate is determined by multiple interacting economic laws. For example, the reallocation of money-capital, in the search for higher returns, has the side-effect of reducing the variance in profit-rates. But technical change occurs at the same time, partly stimulated by the scramble for profit, which has the side-effect of increasing the variance in profit-rates. Hence, empirically I do not expect to see a realised uniform profit-rate (except at very high levels of capital aggregation; e.g. large portfolios of diverse assets that yield an average profit-rate). I derived a candidate functional form for the distribution of industrial profit-rates in this paper: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/A-conjecture-on-the-distribution-of-firm-profit-Wright/d99e859c679fd1e895a5a5df3d17b551ab82c584#citing-papers (as you will see it is highly non-uniform) and Julian Wells’ thesis examines empirical data on the profit-rate and suggests similar functional forms (see http://oro.open.ac.uk/22347/). Nonetheless, to understand economic reality we have to make counterfactual assumptions to isolate different laws that are in play, in order to clearly understand their attractor states. Marx’s analysis of a state of realised uniform profits, with corresponding prices of production, is just such an exercise. This is an economic state that a specific law, if it acted in isolation and without interference, would empirically manifest. But of course it doesn’t. Nonetheless, the law of uniform profit-rates has the consequence of reducing the empirical variance in profit-rates. Hope this is helpful.

Best wishes,

Ian.

LikeLike